Forgive, as You Are Forgiven | A Sermon on Loving Our Enemies

A Sermon by the Reverend Mother Crystal J. Hardin on The Seventh Sunday after the Epiphany (C), February 20, 2022

Genesis 45:3-11, 15; 1 Corinthians 15:35-38, 42-50; Luke 6:27-38

This morning’s readings raise for our consideration the practice of forgiveness and its connection to the command to love our enemies.

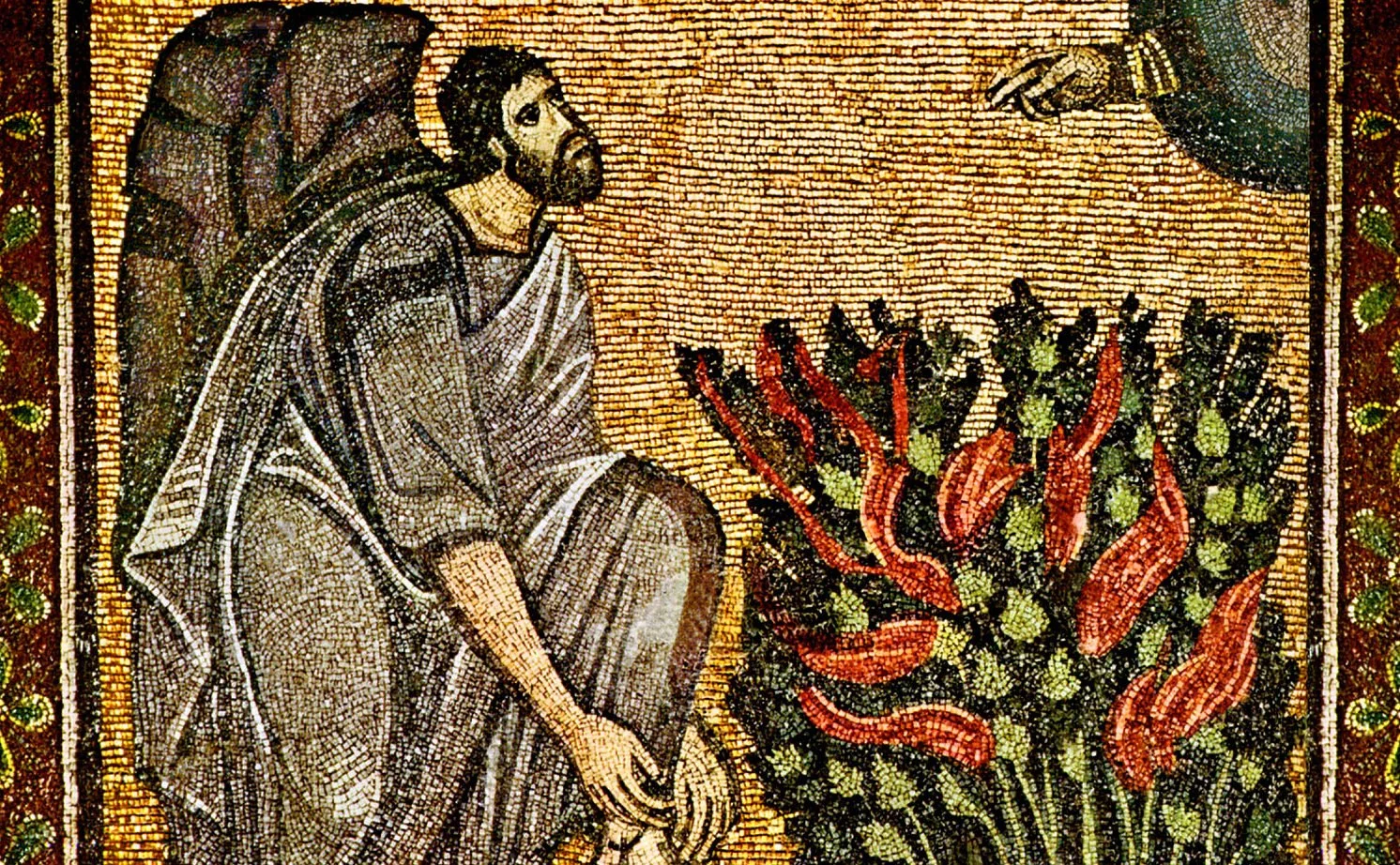

In our first reading, Joseph forgives his brothers for their betrayal, a betrayal that resulted in years of significant hardship.

“Come closer to me,” he asks them. And when they have done this, he tells them, “Do not be distressed, or angry with yourselves, because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life” (Gen. 45:4-5).

The Psalmist cries out to us, “refrain from anger, leave rage alone; do not fret yourself,” why? Because “it leads only to evil” (Psalm 37:9).

And Saint Paul declares that “what you sow does not come to life unless it dies” (1 Cor. 15:36). He is speaking of the Resurrected Body, and yet commentator Debie Thomas notes that there is a word here for those who would consider forgiveness.

Dare I suggest [, she writes,] that those ‘seeds’ might include our resentment, our grudges, our wounds, our prejudices? Paul reminds us that we cannot know ahead of time what God will do with the ‘bare’ and perishable seeds we sow into the ground. All we can do is consent to ‘die’ to everything that hinders new life, and trust that God will raise our dishonor and weakness into glory and power. [1]

And finally, we reach the Gospel of Luke.

Where Jesus said, “I say to you that listen: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those that abuse you” (Lk. 6:27-28).

This is a continuation of the Sermon on the Plain, and it is no less countercultural, no less mind-bending, than the Beatitudes that came before it. The vision cast by these commands is somewhat surreal given what we’ve come to expect from the world we live in, and yet we are called as Christians to open our minds and hearts to this new reality –to let die our ideas of what is possible and impossible when it comes to forgiveness and even love.

This vision, instead, “points toward the power of God’s Spirit to make and remake human life, even in situations that might otherwise seem hopeless.” [2]

I recently discovered a story – a true one as far as I know – that could be said to exemplify this vision. As many of you know, the Armenian people have suffered horribly through the centuries, particularly in a Turkish-led genocide in the early part of the twentieth century. And yet from the Armenian Church comes the following remembrance:

A Turkish officer raided and looted an Armenian home. He killed the aged parents and gave the daughters to the soldiers, keeping the eldest daughter for himself. Sometime later, she escaped and trained as a nurse. As time passed, she found herself nursing in a ward of Turkish officers. One night, by the light of a lantern, she saw the face of this officer. He was so gravely ill that without exceptional nursing he would die. The days passed, and he recovered. One day, the doctor stood by the bed with her and said to him, ‘But for her devotion to you, you would be dead.’ He looked at her and said,

‘We have met before, haven’t we?’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘we have met before.’

‘Why didn’t you kill me?’ he asked.

She replied, ‘I am a follower of him who said, ‘Love your enemies.’ [3]

Many of us, particularly in our current climate, tend to define ourselves more by whom or what we hate than by whom or what we love. And we tend to define forgiveness more as a gift we may choose to offer to those we deem worthy rather than as a holy obligation rooted in the forgiveness freely given to us by God. God whose grace calls and enables us —makes it possible —to forgive and to love, even our enemies.

We love because he first loved us; we forgive because we are a forgiven people.

But how? How are we to love our enemies? How are we to forgive those people, those systems, that have hurt us, have failed us, have oppressed us?

It’s important to first be clear about what forgiveness is and is not.

Forgiveness of the sacred sort is an act of truth telling. It does not deny the goodness that exists in even the most corrupt human heart. And it does not deny the evil that exists among us. It does not deny the significance of the wrong or the pain of it. It takes the wound seriously. In the words of Thomas,

Forgiveness isn't acting as if things don't have to change. Forgiveness isn’t allowing ourselves to be abused and mistreated, or assuming that God has no interest in justice. Forgiveness isn't synonymous with healing or reconciliation. Healing has its own timetable, and sometimes reconciliation isn't possible. . . . In other words, forgiveness is not cheap. [4]

“I am your brother, Joseph, whom you sold into Egypt” (Gen. 45:5). Joseph names himself, claims his identity in relation to his siblings, and speaks clearly of what they have done. Forgiveness is not his first thought, and it will not be his last. Forgiveness is a process. It takes practice. And it does not rely upon the disposition of those to whom it is offered.

In this way, forgiveness is not passive. It is not unexamined. It is not a mind at rest or emotions perfectly in check. It may very well be accompanied by lamentation, righteous anger, and calls for change. There are enemies out there. And these enemies have the power to hurt us and do us harm. Sometimes, these enemies would even call us friends, or, in Joseph’s case, family. And yet, we are called to forgive, because we are called to love. And if we, like Joseph, have the courage to say, “Come closer,” we may very well glimpse not only our own faces in our enemies but the very face of God.

Therefore, we are called not to allow our anger to ossify into hatred and to want for the diminishment or destruction of our enemy. We are called to want for each child of God only flourishing, life abundant. As Martin Luther King, Jr., suggested, “We must love our enemies, because only by loving them can we know God and experience the beauty of his holiness.” [5]

If we truly believe that we were all created for goodness, then we must hold fast to the promise of redemption –for us and for our enemies. If we truly believe that God is making all things new, then we must open our hearts to the possibility that our enemies may repent. In fact, we must want that for them. If we truly believe that Jesus Christ died on the cross for the love of us and for the forgiveness of our sins, then we must, as the late John Lewis so beautifully says,

Anchor the eternity of love in our own souls and embed this planet with goodness. . . . Release the need to hate, to harbor division, and the enticement of revenge. Release all bitterness. Hold only love, only peace in our hearts, knowing that the battle of good to overcome evil is already won. [6]

I’ll end with another story –the story of a celebration of All Souls Day in a refuge in San Salvador.

Around the altar on that day there were various cards with the names of family members who were dead or murdered. People would have liked to go to the cemetery to put flowers on their graves. But as they were locked up . . . and could not go, they painted flowers round their names. Beside the cards with the names of family members there was another card . . . which read: ‘Our dead enemies. May God forgive them and convert them.’ At the end of the eucharist we asked an old man what was the meaning of this last card and he told us this:

‘We made these cards as if we had gone to put flowers on our dead because it seemed to us they would feel we were with them. But as we are Christians, you know, we believed that our enemies should be on the altar too. They are our brothers in spite of the fact that they kill us and murder us. And you know what the Bible says. It is easy to love our own but God asks us also to love those who persecute us.” [7]

The call to love our enemies is a call to face the truth about others and our own capacity to do great good, yes, but also great harm, and yet to struggle to love them, to love ourselves, even in the face of this knowledge.

It is an acknowledgment that we belong to a bigger story, one held in the hands of a redeeming, loving God: “A God who refused (and refuses) to abandon humanity as enemies but sought (and seeks) to transform us into friends.” [8]

It seems to me that W.H. Auden’s poetic verse is as on point as any concluding sentence could be.

If equal affection cannot be

Let the more loving one be me. [9]

Amen.

[1] Debie Thomas, “The Work of Forgiveness,” Journey With Jesus, 13 February 2022, https://www.journeywithjesus.net/lectionary-essays/current-essay.

[2] L. Gregory Jones, Embodying Forgiveness: A Theological Analysis (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1995), 267.

[3] L. Gregory Jones, Embodying Forgiveness, 265-266.

[4] Debie Thomas, “The Work of Forgiveness.”

[5] L. Gregory Jones, Embodying Forgiveness, 263.

[6] Maria Popova, “John Lewis on Love, Forgiveness, and Seedbed of Personal Strength,” The Marginalian, https://www.themarginalian.org/2020/07/18/john-lewis-love-light-forgiveness.

[7] L. Gregory Jones, Embodying Forgiveness, 266.

[8] L. Gregory Jones, Embodying Forgiveness, 267.

[9] W.H. Auden, “The More Loving One.”