Severance | A Sermon for the Sunday of the Passion: Palm Sunday

A Sermon by the Reverend Mother Crystal J. Hardin on the Sunday of the Passion: Palm Sunday (C), April 10, 2022.

Luke 19:28-40; Isaiah 50:4-9a; Philippians 2:5-11; Luke 23:1-49

Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord.

Hosanna in the Highest!

Crucify Him!

I wonder if any of you have discovered Apple TV’s new hit drama, Severance. The show’s premise is science fiction in kind, the show’s characters having agreed to surgically alter their brains so that their work life and their out of work life are held completely separate from one another –one answer, perhaps, to the conundrum of the seemingly impossible “work-life” balance.

Show up at work in the morning, get on the elevator, and, by the time they’ve reached their floor, they’ve essentially become another person entirely –their “work self,” who remembers nothing about what is on the outside or even who is on the outside, including themselves. Their very lives forgotten; they awake into the workday as if they never left. At the end of the day, they punch the clock, get back on the elevator, and arrive in the lobby as they awaken to their out of work selves –remembering nothing about what has transpired at work, including their relationships with coworkers and the very nature of their job or even whether they are happy or fulfilled.

One NYTimes review suggests we “think of it as a neurological mullet: business in the frontal lobe, party in the back.”[1]

A few questions quickly arise. The most interesting one being this: what holds your “out of work self” and your “work self” together–in other words, are you still just one person or somehow two people? And which one is in control of the narrative? Which one is the most real?

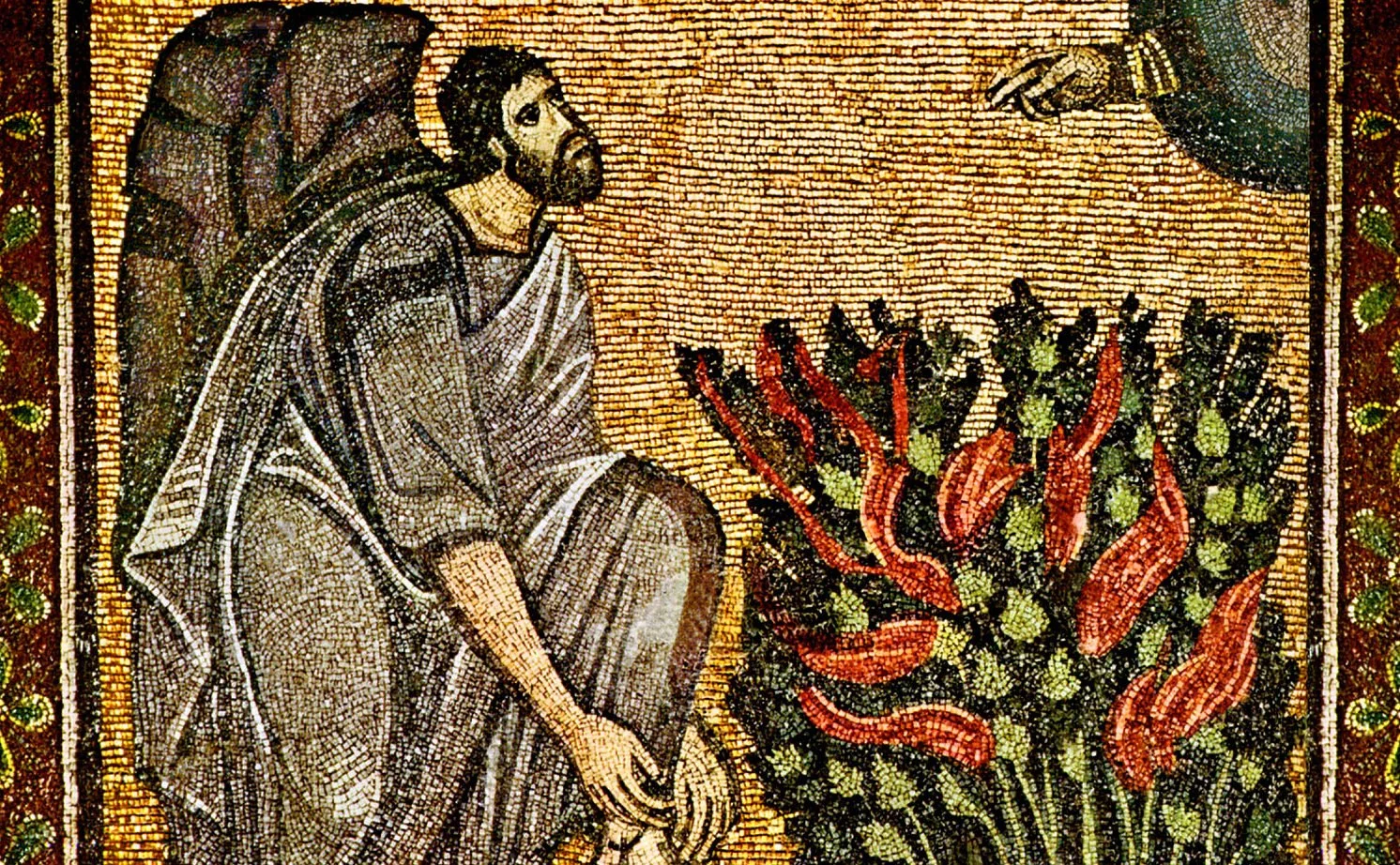

Today, we near the end of the gospel story and are met with the triumphant entry into Jerusalem by the King of kings for which this Sunday is named Palm Sunday. But it does have another name, The Sunday of the Passion, because the story of Jesus’ suffering and death is always read.

This day in the church year, in certain circles, always raises the question of whether we rightly or wrongly read the passion narrative alongside the liturgy of the palms. The jubilant arrival of Jesus and the Cross a bit too jarring to comfortably sit next to one another. The Palm and the Passion at odds.

Hosanna in the Highest! Crucify Him! –making for a discordant sound indeed.

This is why if you do not know what to make of this day, you are not alone –for it casts strange shadows. In the words of Fleming Rutledge:

“Crowds are attracted by the festivity and then get hit over the head with the story of the crucifixion. It is not a day for the faint of heart.”

So, what do we make of these strange bedfellows? And should we act to put them, and ourselves, more at ease?

Perhaps if we severed the two from one another, the transition from Palm Sunday through Good Friday to Easter Sunday would be clearer, easier to follow and to acclimate our minds and hearts to.

If we were to cut the noise, the distraction, we could focus on these two separate events –triumphant entry and crucifixion –more precisely.

But what would be lost?

The truth.

The truth would be lost. The truth about us. The truth about God. And the truth about God’s Grace, which binds the best and worst of us to Him.

This Sunday isn’t meant to feel harmonious. It is meant to jolt us and to drive us, to concern us and to convict us.

Because it speaks a disconcerting truth about us: we, beloveds, can be fickle, quick to hop from movement to movement, savior to savior, love to love (all of those with air quotes by the way). In our search for meaning, happiness, belonging, and love we can miss the mark mightily.

Like the crowd who shouts Hosanna and longs for a king, we too long for a king, someone to save us, and yet do not wish for the king who comes. The crowd longs for a king to set right the civic wrongs, a king to show force and power to their oppressor, a king to save those they believe oppressed, a king to admire and to worship and to serve.

But Jesus is, in fact, not that kind of king. He does not wish to be worshipped and does not want admirers. He wants disciples.

Even as we reenact the crowd’s praise, we reenact their unfulfilled expectations, frustrations, and ultimate betrayal –we know these well in our lives.

And on this Sunday, we are asked to see in the crowd our own propensity for speculation, idolization, wayward action, misplaced anger, and even misplaced hope. Not so that we might sit in our sin (stuck in shame) or celebrate as saints, but so that we might be motivated to reconcile all corners of our lives –the good and bad alike –to the crucified Christ. We are meant to see in Jesus the Christ a Savior, a Grace, a Way where there is no way.

Because we do betray Jesus, then and now. This is the truth about us. And yet, Jesus acted once and for all to save us from ourselves. Jesus forgives us. Each of us. All of us.

You see, the crowd is us, because it is everyone. And Jesus’ Passion was not limited to those who knew him or loved him best. It was a public act, in service to us all: followers, deniers, haters, and lovers alike. Whether you are faithful and dutiful, comprehending or confused, oblivious or all in –Jesus, the Christ, comes for you. This is the truth about God.

And this Sunday, rightly known as “The Sunday of the Passion: Palm Sunday”, is jarring because, even while we see in it the width of human experience, we are met with the depth of God’s love.

Hosanna in the Highest! Crucify Him!

Our ears may well ring and our heads may hurt in considering how these two cries could ever be in relationship, and yet in it is the full spectrum of human experience, the full witness of the Christian life: stubborn hope and hopeless sin met with lavish grace again and again.

Accept your propensity for sin, for betrayal; but do not do it and not also accept God’s love and forgiveness. The reverse, of course, is also true. There is not one without the other. It is our unworthiness that makes God’s grace so extravagant.

This is what the main character in the series Severance comes to know. Mark S. consents to be severed and is glad to do it, because he wants to be free of his grief. His wife died tragically, and he longs to escape his immense pain if even for during the workday. And yet, to sever is to deny. To forget. Not just his pain, but all memory of his wife. Not just grief and loss, but love and life too.

Subjugate one and all is lost.

[1] James Poniewozik, Critic’s Pick: “Severance Review: That Makes Two of You,” The New York Times, 17 February 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/17/arts/television/severance-review.html.